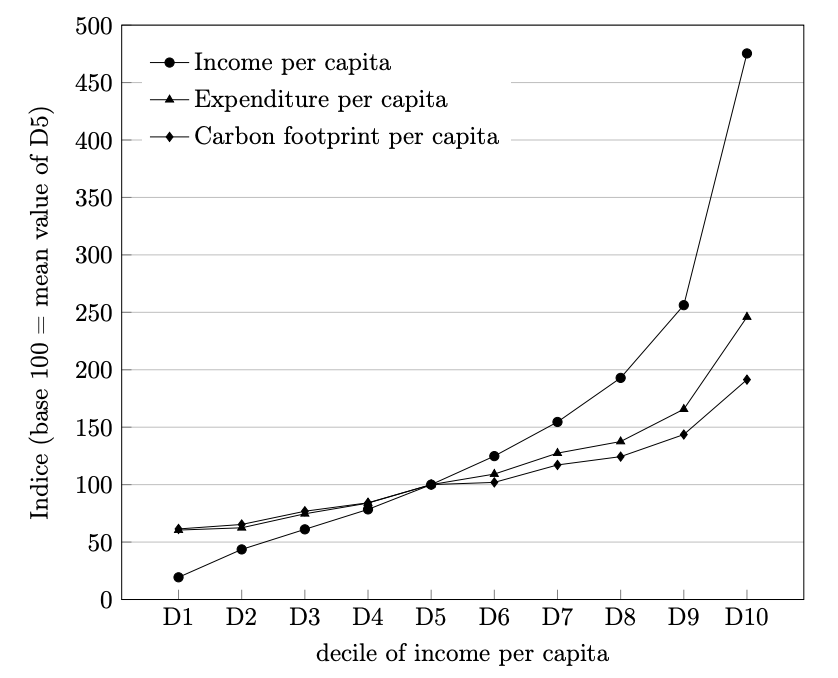

When recently reading The Dispossessed, Ursula Le Guin’s 1974 multi-award-winning sci-fi novel, I kept on coming back to thoughts of the totally equal society theorised by Martin Moryson in his paper proposing that there is an optimum level of inequality for growth (see Optimum Inequality?).

For The Dispossessed features a planet that comes close to delivering on that total equality: Anarres is a land where personal possessions are frowned on, food is shared and eaten communally, and all are expected to give some of their time to menial labour for the benefit of the community. Possession is so frowned on that there are no possessive pronouns: most disconcertingly, there is no way to say “my mother”, she is just referred to as “the mother”, with all the limits to emotional depth of feeling that this implies. Indeed, children are more a community asset than members of a nuclear family. The worst insult on Anarres is ‘propertarian’, a term frequently deployed to shame selfish and anti-communitarian behaviour.

I don’t think it is a failure of Le Guin’s imagination – she had one of the richest and most generous imaginations – that she sees this spirit possible only in a world of dearth and hunger. Anarres has such sparse resources that there is simply no scope for any individual to gather wealth or a disproportionate part of the resources of the planet. It does feature one species of tree (of course, because Le Guin was obsessed with trees) but almost nothing else that is green. It is a dusty, dry planet, panicked by drought and famine a few years back. Its vaunted community spirit didn’t stop some communities commandeering food as it was being transported through for the benefit of others during those hardships. But it is only through that community spirit, sacrifices of individuals to the wider good, and acceptance of hard labour for little reward, that anyone survives on the planet at all. There is no surplus to be possessed by anyone, and not much that could ever amount to personal property, other than the most immediately portable items.

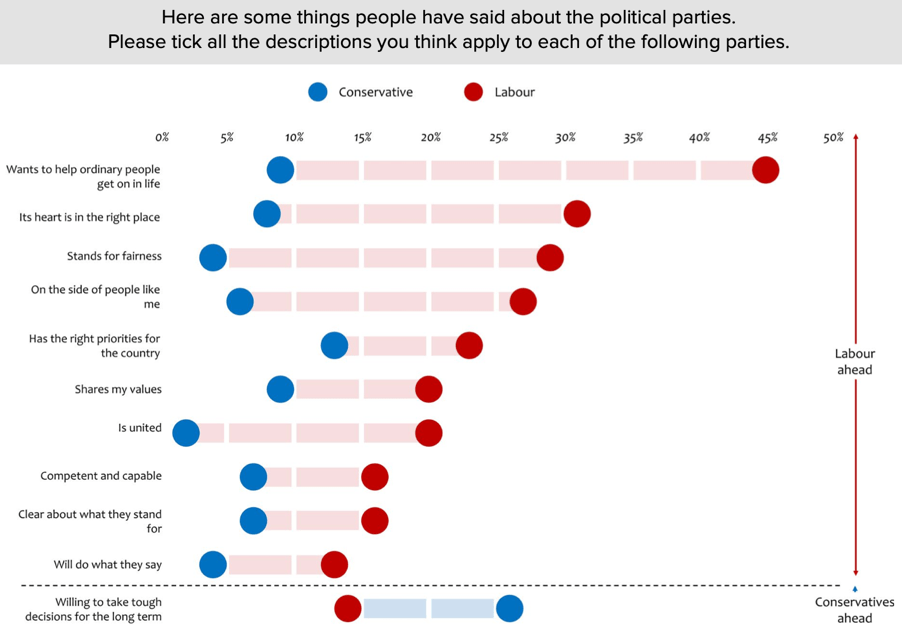

Anarres has a twin planet, a green and abundant one, called Urras. One of the countries on Urras is where the true propertarians live. This is not far from Moryson’s maximally unequal society: some enjoying lives of extraordinarily wasteful consumption and luxury while an underclass suffers and scrapes a bare living. Violence, implicit and sometimes horrifically unleashed, keeps this underclass in check and under constraint. With its controlled media and near constant war with other countries on the planet, there are strong echoes of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Urras is clearly an unfair place. But as I suggested in Optimum Inequality?, neither is the maximally equal society of Anarres fair. The very human trait of personal ambition is constrained, crushed out by near-brainwashing during schooling and in adulthood challenged by social norms and directly in public meetings. Those who refuse to comply are squeezed to the fringes of society, and sometimes deemed mad and committed to institutions. People are not allowed to flourish to their greatest, which seems distinctly unfair. It’s why I don’t think it’s a limitation of Le Guin’s imagination that makes Anarres such a desolate place: only where there is no chance of surplus, she implicitly says, will human beings accept such constraints on their personal lives and scope for personal advancement, including hopes for a better life for ‘their’ children.

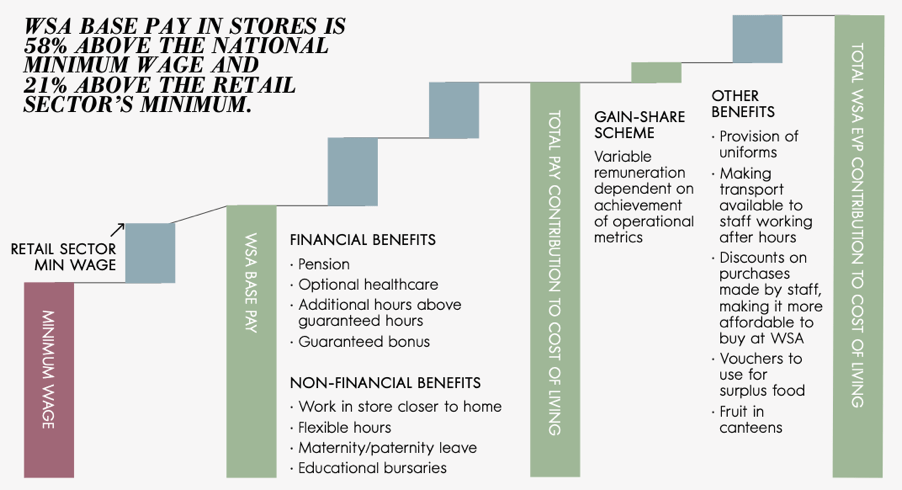

If we want a fair world – and one of the central precepts of this blog is that humans do, viscerally and by our very nature, want a fair world – we need to navigate the realities of abundance but find better ways of sharing that abundance than we currently do. It would not be fair, it would not be human, to have as equal a society as that of Anarres. But we need to move nearer towards it than we currently are, which is closer to the unfair inequalities of Urras – both to deliver greater economic growth, as Moryson argued, and to fulfil our collective and visceral need for a fairer world.

By the way, if you haven’t read any Le Guin, I wouldn’t start with The Dispossessed. I’d start almost anywhere else, but certainly with the Earthsea books and with her short stories, collected as The Wind’s Twelve Quarters and The Compass Rose. Among her sci-fi novels, the extraordinary The Lathe of Heaven is my personal favourite. In all of her best fantasy and sci-fi creations, of distant and different worlds, she brings us back to a closer understanding of what it is to be human, with deft and quiet moments of beauty and gentle kindness. And there are always trees.

See also: Optimum inequality?

The Dispossessed (1974), Ursula K Le Guin

Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), George Orwell

A Wizard of Earthsea (1968), Ursula K Le Guin

The Tombs of Atuan (1971), Ursula K Le Guin

The Farthest Shore (1972), Ursula K Le Guin

Tehanu (1990), Ursula K Le Guin

Tales from Earthsea (2001), Ursula K Le Guin

The Other Wind (2001), Ursula K Le Guin

The Wind’s Twelve Quarters (1975), Ursula K Le Guin

The Compass Rose (1982), Ursula K Le Guin

The Lathe of Heaven (1971), Ursula K Le Guin

All are available at good bookshops – which (particularly if you care about paying fair levels of tax) doesn’t include Amazon