“For me the question now after six months of the outbreak, the question remains to the elders and decision-makers, what kind of world are you leaving for us? Is it fair that we inherit this unequal, violent, empty of values world? We are paying for a system we did not co-design and yet we are inheriting this anyway.”

So said Aya Chebbi, the African Union’s first Youth Envoy, at the Tortoise G7bn Summit in September. Where youth has a voice, it is already calling older people to account. If we listen, we are being reminded that we have not been, and are not being, good ancestors.

The challenge of intergenerational fairness is one that our world is currently failing. A recent WHO-UNICEF-Lancet report, A Future for the World’s Children?, found that current policies are failing future generations in every country in the world. Bluntly, it reports that in spite of the dramatic improvements in survival, education, and nutrition for children worldwide over the last 50 years, meaning that “In many ways, now is the best time for children to be alive”, nonetheless “economic inequalities mean benefits are not shared by all, and all children face an uncertain future. Climate disruption is creating extreme risks from rising sea levels, extreme weather events, water and food insecurity, heat stress, emerging infectious diseases, and large-scale population migration. Rising inequalities and environmental crises threaten political stability and risk international conflict over access to resources. By 2030, 2.3 billion people are projected to live in fragile or conflict-affected contexts.”

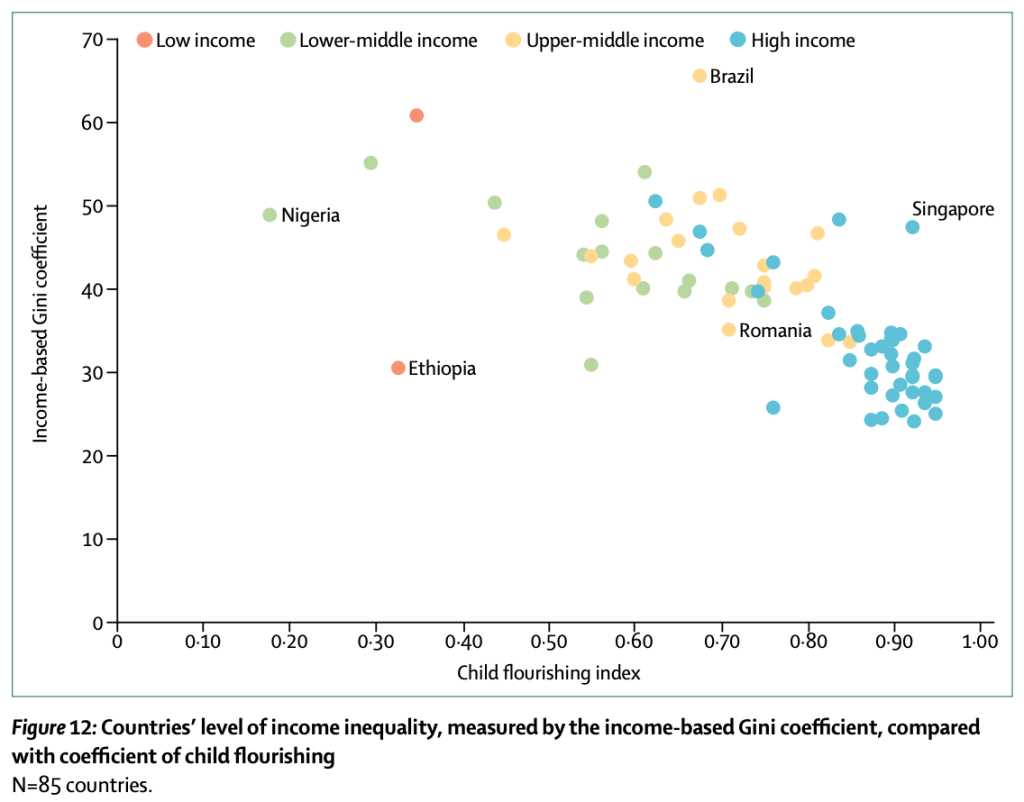

One chart from the report is particularly stark, showing a clear correlation between income inequality and measures of child flourishing (data newly synthesised for the report), particularly relative to countries of a like income bracket. “Equity [fairness] is essential to ensure that efforts to promote children’s present and future flourishing truly leave no one behind,” it notes. There is an implication for global fairness from this analysis: if global inequity worsens, so will the prospects for our children; conversely if we can improve fairness we have the opportunity to enhance the prosperity and wellbeing of all.

The WHO-UNICEF-Lancet team suggest that children’s interests should be placed at the heart of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the UN’s ragbag charter of 17 global development aims for the 15 years from 2015, from zero hunger and clean energy to climate action and responsible consumption. “Fundamentally, the SDGs are about the legacy we bequeath to today’s children. For that reason alone, children should be placed at the centre of the SDG endeavour,” the report suggests. It also references the General Comments to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which includes the right to “Be treated fairly”. Our record against the SDGs suggests we are not succeeding in fair treatment.

But this is not a challenge for developing economies only, and not a challenge that only developing economies are failing. Intergenerational unfairnesses are stark in many developed economies. Take the Resolution Foundation’s Intergenerational Centre statistics for the UK, as exemplified in the following chart from their excellent interactive data dashboard tool. This shows relative poverty after housing cost over time for the population as a whole (olive line), the over 65s (sage line), the under 17s (pink line) and those from 16-29 (purple line):

While the headline poverty number for the population has risen somewhat, from around 13% in 1961 to just under 20% in 2017, this masks radically different experiences for different portions of the population. The pension aged population has gone from a scandalous 40% living in poverty to around 15%, while the proportion of children living in poverty has nearly trebled from just over 10% to just under 30%. But the trajectory of the 16-29 age group is perhaps most startling: having seen by far the least poverty in 1961, at only 4%, they are now well above the population average at 22% in 2017 (and 27% as recently as 2012).

As Aya Chebbi’s comment indicates, there is a short-term, virus-related element of these unfairnesses, and also a longer-term aspect, particularly in relation to the scale of the climate crisis. Taking the immediate issue first, it is clear that Covid-19 will further erode fairness between generations. As can be seen from this chart from Resolution Foundation’s recent intergenerational audit, there is a stark age effect in furloughing, and still more so in jobseeking. And it is set to worsen further: Office for Budget Responsibility estimates see unemployment for the 18-29 age group spiking to 17%; older groups are expected to see unemployment no worse than 7% (though of course that is bad enough). While these statistics are for the UK, the experience is likely to be universal given the jobs usually taken by the young — both less stable and skewed towards sectors hardest hit by the virus and the constraints it places on our lives. Some of this is inevitable, but it could be mitigated better.

We are making life harder for the generations that come after us. That’s the opposite of what we are called to do.

In his reactionary 1790 diatribe against the French Revolution, Edmund Burke chastised those who do not recognise that “we are temporary possessors and life renters” of our world and our society. He criticised those who are “unmindful of what they have received from their ancestors, or of what is due to their posterity” and instead “act as if they were the entire masters”. He charged that we “should not think it amongst [our] rights to cut off the entail, or commit waste on the inheritance”.

While that was a highly conservative message, it is clear that refusing to change can in some circumstances cause just as much damage to future generations as can revolutionary change.

It is the very heart of good stewardship to build in thoughts about the future. As temporary possessors, we are all called to operate with consciousness of the needs of the future rather than assuming it will be able to look after itself. Life renters must find a way to resolve the tension between short-term pressures and longer-term needs. For example, Edward Laurence in his 1727 The Duty of a Steward to His Lord (which I elsewhere identified as The Original Stewardship Code) discouraged the use of clay for bricks as that depletes the land; similarly, he charged that stewards should not sell off timber that rather needed be retained for use as building material within the estate. His tome is almost obsessed by maximising the availability of fertiliser to enrich the estate’s soil for the future.

However, instead of acting as good stewards in this way, we continue to deplete the world’s resources on a Micawberish assumption that something will turn up.

More recent thinkers have reached similar conclusions. In 1977 economist John Hartwick set out what has become known as the Hartwick Rule of intergenerational equity. He stated that “to ensure intergenerational equity, society should invest enough of the rental income from extraction and use of exhaustible, and thus naturally scarce, resources so that future generations would benefit as much as today’s”. As the World Bank puts it in The Changing Wealth of Nations: Measuring Sustainable Development in the New Millennium (2011): “The Hartwick rule holds that consumption can be maintained — the definition of sustainable development — if the rents from non-renewable resources are continuously invested rather than used for consumption.”

John Rawls, the great thinker on fairness whose ideas have become decidedly unfashionable as the liberal American postwar economic success that he sought to justify has receded from view, posited a similar just savings principle. This argues that there is a duty to save justly such that future generations enjoy at least the minimal conditions necessary for a well-ordered society. In other words, we must not consume so much now that it is at the expense of future generations, instead we should set aside savings to benefit future generations. This goes one stage beyond Hartwick because it contemplates not only avoiding a negative such as limiting depletion of scarce resources but also actively pursuing positive measures, including investment in education and technology.

The perceived limited resources have changed over time. Once it was wood or mineral wealth. Now the most urgent limitation is seen to be the capacity of our atmosphere to absorb further CO2 and other greenhouse gases without further increases in global temperatures. There is some investment in technology to mitigate carbon intensity, but many doubt it is anywhere near sufficient. But the philosophical mindset remains the same: we have a duty to our successors not to bequeath them a worse world. We are failing in that duty currently.

Some are at least considering how the interests of future generations can be more fully built into policy-making and current planning. “The fear is that today’s adults are mortgaging our children’s future; taking too many policy decisions with an eye to short-term benefits while disregarding the long-term harms. In the years ahead, the sense of intergenerational tension is set to intensify, with more generations alive simultaneously and tightening availability of limited resources, from ecological resources such as water and forests to pensions savings,” say Cat Tully, the School of International Futures and Luis Xavier, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, in a June 2020 article on designing policies that are fair to future generations.

They highlight the 4 key principles and approaches to intergenerationally fair policymaking identified by the Gulbenkian Foundation’s Intergenerational Fairness initiative. These offer a method for discerning policies that do deliver fairly between generations. They are written for the world of public policy, but applicable with some sensible adjustment to help shape corporate strategic thinking (essentially, all are about giving space for the interests of neglected stakeholders to be considered):

- Run regular “national conversations” to (a) engage the public in exploring possible futures for their country, and (b) devise the detailed measures of intergenerational fairness for the framework.

- Give immediate responsibility for “vetting” policy for its fairness or unfairness to an independent government body or bodies.

- Put in place the wider conditions to lock in the institutional and public pressure for the new framework to work.

- Activate “outside-in” (public-on-government) pressure.

Some business leaders are already trying to give effect to such a mindset. Dan Labbad at the British Academy’s Future of the Corporation Purpose Summit referred to future generations as “arguably the most important stakeholder” for his business. But, given he is CEO of the Crown Estate, which runs the assets of the British nation’s monarch, he has an unusually long time horizon for operations, not least as “We have a statutory obligation to protect, maintain and enhance the estate into perpetuity”. Nonetheless, he argues that future generations are an important stakeholder common to all businesses, “often neglected, but crucial”:

“While they don’t get to hold us to account today they are the recipients of what we leave behind. That’s why our purpose at the Crown Estate will be guided by the creation of something that ultimately represents them and their interests to ensure that they are more than mere recipients but ultimately beneficiaries, inheriting something that will be the foundation of their future, a legacy that they’ll be proud of. I strongly suggest we take their role as a stakeholder seriously and as a humble reminder of why we need to operate with purpose in the first place.”

Building the interests of future generations into our decisions now is something we seek to do (not always successfully) when we think about our own children, and grandchildren. But we struggle to do it on a grander scale, and yet we need to. Certainly, most business fails to live up to this demand. Instead, we are mortgaging future generation’s inheritance now, and that is not fair. We are bequeathing a worse world, not a better.

Where youth has a voice, it is holding older generations to account for their unfairnesses. We need to ensure that youth has a voice, and that their voice is heard, so that they can begin to help co-design their own future. As we have failed to do so in the past it is perhaps not surprising that we have caused so much damage to their future, notwithstanding the longstanding calls to operate with a long-term mindset that does provide them with a fair world to grow up into.

“Is it fair that we inherit this unequal, violent, empty of values world? We are paying for a system we did not co-design and yet we are inheriting this anyway.”

I am grateful to my friend Peter for challenging me to write about this topic finally, and flagging up the article on apolitical (sorry it’s taken a while!)

The Good Ancestor, How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World, Roman Krznaric, 2020

A future for the world’s children? WHO-UNICEF-Lancet, February 2020

Resolution Foundation Intergenerational Centre

An intergenerational audit for the UK, Resolution Foundation, October 2020

Reflections on the Revolution in France, Edmund Burke, 1790

The Duty of a Steward to His Lord, Edward Laurence, 1727

The Changing Wealth of Nations: Measuring Sustainable Development in the New Millennium, World Bank, 2011

How to design policies that are fair to future generations, Cat Tully, Luis Xavier, apolitical, June 2020

Gulbenkian Foundation Intergenerational Fairness initiative

What is the role of stakeholders in purposeful business?, from the Future of the Corporation — Purpose Summit, British Academy