Lex Greensill’s promise with his eponymous supply chain finance business was to readdress the balance between suppliers and their customers – customers which are often much larger and set terms that are markedly favourable to themselves. As set out in chapter 20 of the excellent and highly recommended book Pyramid of Lies on Greensill and how his business collapsed into scandal under the weight of undelivered promises, that’s not how it turned out.

Instead, author Duncan Mavin argues, Greensill made finance less fair.

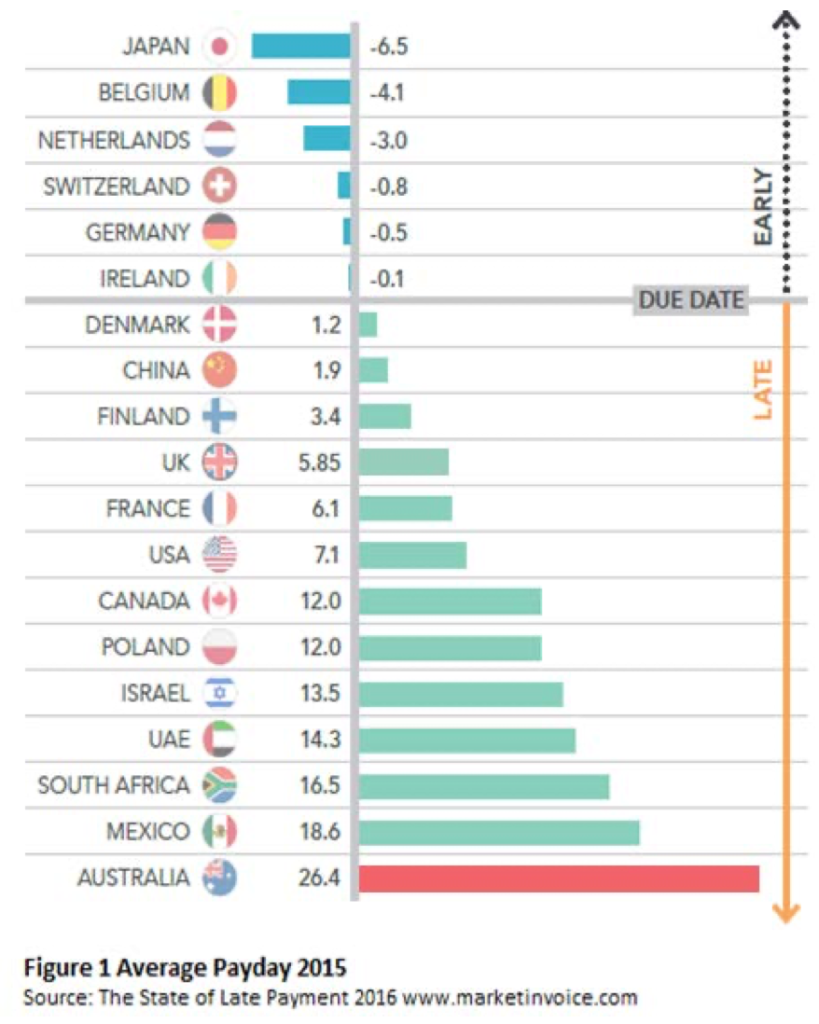

In the chapter, Mavin’s main evidence for arguing the unfairness of supply chain finance is the excellent work by the Australian Small Business and Family Enterprise Ombudsman (painfully abbreviated as ASBFEO). Its 2017 Payment Times and Practices Inquiry Final Report noted the country’s poor treatment of small suppliers – as the chart below suggests, Australia was a particular outlier but far from alone in seeing larger businesses taking advantage of their supply chains. Most of ASBFEO’s recommendations in that final report were addressed to the Australian government – urging among other things that the government offer 15-day payment terms as standard, and require its own head contractors to offer the same terms also (which seems sound, and fair, advice to other governments). Its recommendations to industry more generally led to the creation of the voluntary Australian Supplier Payment Code. This was launched in 2017 and has been reviewed since, the latest version dating to 2021.

The core requirement of the voluntary Code is that Australian suppliers should be paid within 30 days. But the ASBFEO in its March 2020 Supply Chain Finance Review Final Report highlights that supply chain finance schemes, including those provided by Greensill, enabled this basic standard to be evaded and suppliers in effect to be obliged to accept different terms even while signatories could claim adherence to the Code. The Ombudsman called for greater transparency, in particular for any requirement to use supply chain finance, and for greater regulatory attention on supply chain finance, both its potential to exploit data on suppliers and the possible regulation of the form of finance overall.

The report specifically references promises that Greensill made as a response to the ASBFEO’s work on supply chain finance. It states: “Greensill Capital have announced that they will not allow their product to be used by large businesses that push out payment terms to SME suppliers beyond 30 days,” as well as quoting Lex Greensill himself referring to this sort of activity by large companies to be “bullying” of their smaller suppliers.

Bullying of the supply chain is clearly not admirable or fair behaviour. It isn’t likely to be sustainable in the long-term as suppliers are likely to seek customers that offer less on-sided relationships – or may risk themselves not being sustainable in the long-run. But sadly it appears to be prevalent, not only in Australia.

In addition, among the evidence to the ASBFEO in its review is further confirmation of what I have previously called the economic madness of the whole supply chain finance offering. Local provider TIM Finance in its letter in response to the review, states:

“[Supply chain finance], when implemented and used properly, provides huge benefits to Suppliers as they are sourcing funding (by being paid early) by taking advantage of the cost of funds based on the Buyers [sic] credit rating. The annualised discounts that a Supplier ‘endures’ by accepting early payment needs to be equal to or less than the cost of funds of that Suppliers [sic] sourcing a funding facility (business loan) themselves from a bank or non-bank lender.”

This confirms the simple point that supply chain finance relies on the lower pricing of finance on offer to the large company that is the customer – the ‘cost of funds based on the buyers’ credit rating’ – in comparison to that available to the supplier. The supply chain finance provider takes its profit margin out of that differential. As well as being fairer, the cheaper route for the system overall would be for the financing of the supply chain to come predominantly from the customer, taking advantage of its lower cost of finance, without a further intermediary taking a margin from it. If customers didn’t stretch the payment terms required of their suppliers, then there would be less cost in the system overall.

The removal of Greensill Capital from the market – and the disgrace in which it has exited – may have brought this sort of offering into some further disrepute, which the Australian Small Business and Family Enterprise Ombudsman would suggest is wholly deserved. The new accounting standard requiring further disclosures may also reduce some of the perceived advantages for this sort of financing. The evidence is that this would be less economically wasteful, as well as representing fairer finance.

See also: Demanding Supply

Pyramid of Lies, Duncan Mavin, Macmillan, 2022

Note for UK readers: the subtitle (presumably only for the UK market), ‘The Prime Minister, the Banker and the Billion-Pound Scandal’ isn’t really delivered on; David Cameron remains largely a peripheral figure throughout. The book is none the worse for that.

Payment Times and Practices Inquiry – Final Report, Australian Small Business and Family Enterprise Ombudsman, 2017

Australian Supplier Payment Code, Business Council of Australia, 2021

Review of the Australian Supplier Payment Code, Business Council of Australia, 2019

Supply Chain Finance Review – Final Report, Australian Small Business and Family Enterprise Ombudsman, March 2020

Feedback on the Supply Chain Finance Review – Position Paper, TIM Finance, February 2020

Supplier Finance Arrangements, International Accounting Standards Board