The Amazon is a remarkable space, both for its beauty and biodiversity and for the global service it performs as the lungs of the world. If it were not subject to mass deforestation it would be a substantial carbon sink in a world desperately in need of places to swallow our rising levels of carbon dioxide.

We’ve seen two pieces of news about the Amazon in recent weeks, neither of them told with complete accuracy. First was the news about a decrease in deforestation in Brazil, which was celebrated by many. Of course, it is a positive sign that the new political regime under President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva can reduce the most negative impacts of his predecessor’s free rein populism, but deforestation continues; it is just that its speed has reduced. We are some way away from the true reversal of the damage done to the Amazon under President Bolsonaro. Fears persist that the Amazon may be reaching a point of no return and this news leaves the rainforest heading in the wrong direction.

The second piece of news was the Belem Declaration, an agreement between the 8 countries that contain the Amazon region within their territories, signed on August 9th. We were told that this was a failure because it did not contain what President Lula apparently hoped for: an international deal to end Amazon deforestation by 2030. The Declaration is nonetheless a notable achievement (any agreement between 8 different countries with very different politics is notable), containing no fewer than 113 objectives and principles. It is also a document that teaches us a great deal about where we are in terms of the geopolitics of climate.

A lack of fairness is central to what hinders us in reaching international deals to constrain future carbon emissions and boost the health of carbon sinks. The Belem Declaration makes clear that any global climate deal needs to think deeply about how to embed fairness. We’re heading towards COP-28 in Dubai. I don’t personally have great hopes that a good deal will be struck there, because the world’s leaders don’t yet seem to have learned this lesson about fairness. I do hope to be proved wrong.

Fairness is explicitly central to the Belem Declaration. The document starts:

“Aware of the urgency of the challenge of the full protection of the Amazon, the fight against poverty and inequalities in the Amazon and the promotion of sustainable, harmonious, integral and inclusive development in the region”*

The language of fairness recurs throughout the preamble, including for example in a section about the importance of women’s rights and perspectives: “Recognising that women and girls are disproportionately affected by the adverse impacts of climate change and environmental degradation, and that their participation in decision-making is critical to sustainable development, the promotion of peaceful, fair and inclusive societies and the eradication of poverty, in all its forms and dimensions.”

President Lula’s reported 2030 ambition for ending deforestation is in fact visible in the Declaration, stated as an ‘ideal’ of zero deforestation by that date. The Declaration also mentions the aim of eradicating and stopping the advance of illegal logging. However, it isn’t hard to read between the lines to see why that simple ambition wasn’t formally agreed at the summit: throughout the document it talks about the need to balance the interests of local populations, particularly indigenous people, and the need for sustainable economic development for the people of these developing economies. The Declaration seems to talk less about the need to protect the rainforest for the benefit of indigenous peoples, and more about how those indigenous peoples can fairly enjoy some economic development, acknowledging that this needs be sustainable development. The fact that 2030 is also the timeline for delivering the UN Sustainable Development Goals seems implicit in the thinking about Lula’s deforestation ambition.

The call for fairness in sharing of resources, and the scope for less developed economies to enjoy development notwithstanding the climate challenge, is especially clear in the Climate Change section of the Declaration. This includes a number of very specific asks of wealthy nations, including paragraph 35 which urges developed economies to bring forward their financing, especially the promised $100 billion a year for developing economies to support their delivery of climate actions. Similarly, paragraph 36 calls for innovative financing for climate actions, including potentially the exchange of debts in return for climate actions.

For many of us, it remains a frustration that politicians continue to emphasise the costs of the climate transition without any apparent attention to its economic opportunities (let alone the costs of inaction), but that is clearly where the political thinking remains for the time-being. And in large part, the reason for this is the unfairness of how climate impacts are shared, particularly when compared to historic and current emissions, and indeed capacity to pay, as this chart from this year’s Climate Inequality Report starkly shows:

A clearer visualisation of why the political process on climate is stuck would be hard to find.

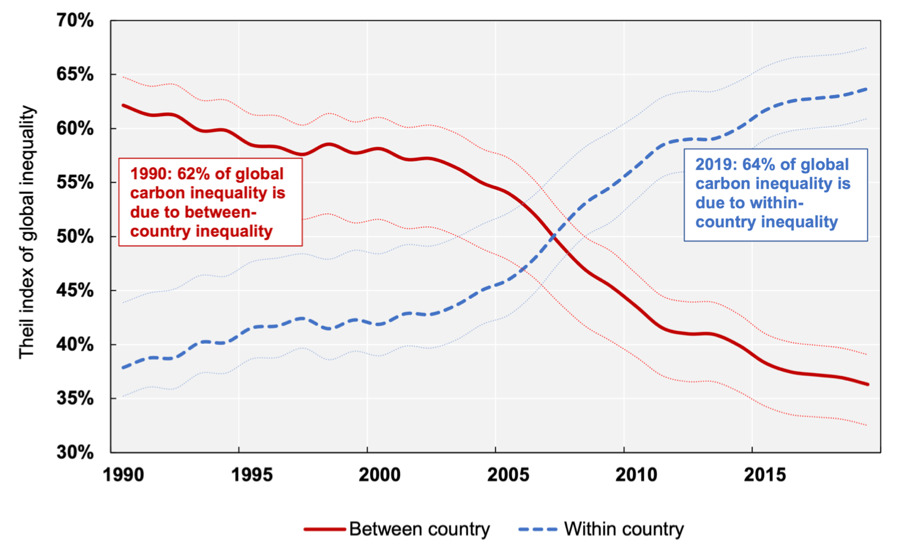

The polluters need to pay, but at present they feel limited incentive to do so. Of course, as well as the inter-country unfairnesses in carbon emissions, there is remarkable unfairness in emissions within country too (see Unfairness in carbon emissions) – and as of the last two decades this is now the greatest driver of carbon inequality, according to the Climate Inequality Report’s chart below:

But it is the still very substantial unfairness between countries that makes political progress so difficult.

It cannot be by chance that the Belem Declaration contains a statement of support for Brazil’s bid to host the COP-30 climate summit in 2025 – accompanied by a note that the progress from this year’s COP-28 to COP-30 “will be critical to the future of the global response to climate change” [isn’t every one of the next months and years?]. The bid is to host the COP in Belem itself; one hopes that the symbolism of holding the event in the Amazon has an appropriate effect.

This is the South’s agenda: you cannot ask us to act alone. We need help and assistance. Until the North responds, not just with words but with real cash, systematically and at scale, the politics will remain blocked. Whether the requirement will be at the scale of the annual $300 billion global wealth tax floated in the Climate Inequality Report will have to be seen.

But it is clear that unless we address inequalities we will not reach the political agreements needed for a global approach to the climate challenge. We need fairness to find a global solution that takes the world forward. Without fairness – or at least without less unfairness – we will not progress.

* Note that, here and elsewhere in this blog, this is an informal translation; the declaration is only officially published in Portuguese and Spanish.

See also: Unfairness in carbon emissions

Just transitions and gilets jaunes

Sea level rise: the most unjust transition

Press notice on the Belem Declaration, Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization, 9 August 2023

Belem Declaration, August 2023

Climate Inequality Report 2023: Fair taxes for a sustainable future in the Global South, Lucas Chancel, Philipp Bothe, Tancrède Voituriez, World Inequality Lab, January 2023

Just Nature: How finance can support a just transition at the interface of action on climate and biodiversity, Sabrina Muller, Nick Robins, Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, August 2022