It shouldn’t really be a surprise, but dignity at work – a combination of things such as the sense of autonomy and relationships with colleagues and bosses, and being treated fairly – matters to people. It’s as true at the bottom of the income scale, where observers might assume concerns about pay outweigh all other considerations, as it is higher up. Dignity matters to people, as I’ve been exploring in recent blogs.

For the book I am writing (on fairness in business and investment) I am currently investigating the literature on monopsony and oligopsony in labour markets. Monopsony is the distorted market situation arising from there being a single buyer of a good or service (a monopoly is where there’s a single seller); oligopsony is where there is a narrow enough group of buyers that they distort the marketplace. Economists are increasingly observing evidence that the labour market suffers inefficiencies that are consistent with oligopsony – employers having excess power in setting pay. Most workers would probably agree that their experiences too are consistent with this.

One part of this literature particularly stood out because it made a link to the issue of dignity, which increasingly seems a key element of people’s innate sense of fairness, and of their inclusion in society and the economy. In particular, a 2022 paper from the US National Bureau of Economic Research, called Power and Dignity in the Low-Wage Labor Market: Theory and Evidence from Wal-Mart Workers, uses evidence from real interactions with US employees of the globe’s largest private sector employer to understand their views and test hypotheses against reality.

The results are striking.

The study included four sentences exploring the degree to which workers had a sense of dignity in their jobs (these sentences were developed based on prior interviews with Wal-Mart workers that sought to understand their experience in the workplace, as well as earlier academic work). The overarching question was Indicate to what extent the sentence describes the workplace of your job at Walmart, and each time respondents were offered four responses (Almost Always; Often; Sometimes; Never). The four sentences were:

- You [have/had] the opportunity to express yourself while at work.

- You [can/could] rely on your co-workers to help you with work.

- Your supervisor [treats/treated] you with respect.

- Your supervisor [treats/treated] everyone fairly.

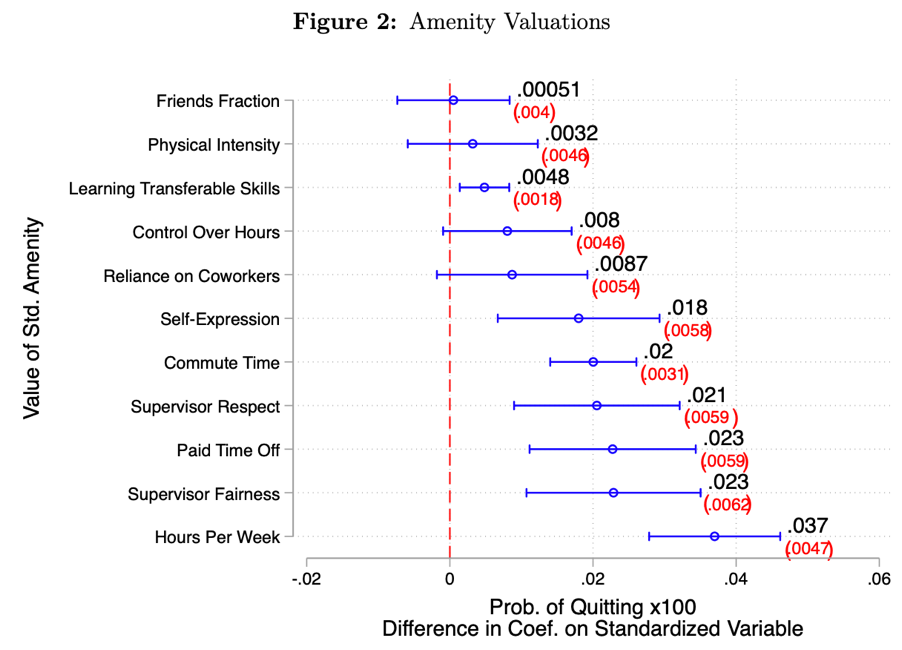

And of these four measures of dignity, it appears to be fairness that matters most. Indeed, a lack of fair treatment by one’s boss is in essence the greatest determinant of likelihood of quitting a job in the study, with the obvious exception of pay (and of the availability of hours of work a week, which is a clear part of the pay equation for those paid on an hourly basis):

Consistently, the study confirms that fairness and dignity are powerful drivers of work satisfaction, and thus in willingness to stay with an employer.

As the study states:

“A natural question is whether firms can adjust the level of dignity at work. While immediate supervisors likely have the most discretion over workplace dignity, supervisors can be incentivized by higher-level managers to treat subordinates fairly and with respect, and workplace rules can be designed to allow opportunities for self-expression and co-worker support. While it may take time to alter workplace experiences, and agency costs might be considerable, the significant cross-store variation we document below suggests that managers have some control over the level of workplace dignity.”

Our bosses, and how they treat us, matter.

As well as enhancing people management, the authors raise the interesting challenge of whether improving the competitive context of the labour market is necessary to increase dignity in the workplace, the experience of fairness for workers:

“any effort to increase workplace amenities (including subjective experiences at low-wage jobs) may require policies that reduce monopsony power in the low-wage labor market. The high levels of labor market competition in the immediate post-COVID labor market may have given workers the opportunity to quit jobs that didn’t provide dignity. Whether this results in firms upgrading the subjective experience of work remains to be seen.”

I’m not sure that we’ve yet seen significant enhancements to workplace dignity and fairness, but perhaps we should continue to live in hope.

See also: An inequality in dignity, or the dignity deficit

Belonging, not belongings

I am happy to confirm as ever that the Sense of Fairness blog is a purely personal endeavour

Power and Dignity in the Low-Wage Labor Market: Theory and Evidence from Wal-Mart Workers, Arindrajit Dube, Suresh Naidu, Adam Reich, NBER Working Paper No. 30441, September 2022