Even given my cynicism regarding the current hype about artificial intelligence (AI)*, I have to admit that it’s very clear this new technology will transform the world of work. The societal excitement about Chat GPT and other large language models (LLMs) has been matched by corporate excitement. Companies across the world are experimenting broadly, many of them keen to deploy this as a cost-saving tool.

Of course, as with every technology shift, cost-saving comes in the form of replacing people with machinery. Efficiency means being able to do things more quickly with less human intervention. If the current experiments with AI deliver, perhaps companies will redeploy those humans to other work. More likely they will remove those people, and their costs, from their business.

That’s how business, and economies as a whole, operate: moving to more efficient ways of delivering what customers and society want, to enable higher profits or simply to enable companies to compete with rivals which are also trying to reduce their costs. On the whole, this is good for economies too as more efficiency allows national resources to the deployed to where they deliver most value.

But that redeployment takes time, and technology transitions are painful processes, for individuals and for society. Discussions of efficiency, cost savings or redeploying resources divorce us from the very real human and emotional impacts of these changes, which are of individuals losing their jobs and livelihoods, and subsequently struggling for money and self-esteem. Even where a technological shift does create new opportunities (which has been the case with every such transition previously and so seems likely once again), that takes time – time in which individuals feel unanchored, unvalued, and perhaps reach an age where further employment is unavailable to them. That can serve to destabilise society further. We shouldn’t let the economics blind us to the personal and emotional.

There is much talk in sustainable investment circles of the need for a just transition (sometimes a fair and just transition) to a decarbonised world, ensuring that care is taken to protect and support those individuals whose jobs are impacted by the dramatic shift to economic activity that must come as the world finally faces up to the realities of climate change. There is also likely to need to be a fair and just transition to an AI-enabled world.

Recent work from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) begins to open a window on this challenge, building on the sentiment of managing director Kristalina Georgieva in a blog from a year ago called AI Will Transform the Global Economy. Let’s Make Sure It Benefits Humanity. The organisation is developing approaches to consider which jobs – and which economies overall – will be impacted by the advent of AI.

Most recently, IMF staff considered impacts in Asia. A blog this month, How Artificial Intelligence Will Affect Asia’s Economies, tries to map this out in more detail, based on analysis of the breakdown of jobs in each economy. The blog reflects a deeper discussion within the analytical note attached to the Fund’s most recent Asia and Pacific Regional Economic Outlook. This analysis suggests a greater exposure to AI impacts in the region in what IMF jargon terms advanced economies, while emerging economies are likely to face lower impacts. However, they also seek to assess whether those impacts will be positive or negative for jobs: around half the impacts in advanced economies are where AI is complementary to the job, potentially driving economic benefits; meanwhile in emerging economies the majority of impacts are where there is much more likelihood of workers finding their jobs replaced. The economists hedge this analysis with language such as ‘low complementarity’ and ‘displacement’ of work, but the thinking is clear.

The language was more blunt in some earlier less detailed work, suggesting AI “could endanger 33 percent of jobs in advanced economies, 24 percent in emerging economies, and 18 percent in low-income countries”. Those conclusions look more worrying than the most recent analysis, but even the lower levels of estimated disruption are very significant.

According to the most recent analysis, there is also a gendered split in the potential impacts, again potentially exacerbating existing inequalities:

The blog reads:

“The concentration of such [complementary] jobs in Asia’s advanced economies could worsen inequality between countries over time. While about 40 percent of jobs in Singapore are rated as highly complementary to AI, the share is just 3 percent in Laos.

“AI could also increase inequality within countries. Most workers at risk of displacement in the Asia-Pacific region work in service, sales, and clerical support roles. Meanwhile, workers who are more likely to benefit from AI typically work in managerial, professional, and technician roles that already tend to be among the better paid professions.”

Georgieva was clear about the risks: “In most scenarios, AI will likely worsen overall inequality, a troubling trend that policymakers must proactively address to prevent the technology from further stoking social tensions.”

The IMF economists are increasingly clear about what needs to be done about these inequality risks. According to them, a just transition will require:

- Effective social security nets

- Reskilling programmes for affected workers

- Education and training to enable effective application of the AI opportunity, particularly for those economies where AI is currently seen to have low impacts – so that the positive benefits can be enjoyed

- Regulation to promote ethical AI use and data protection

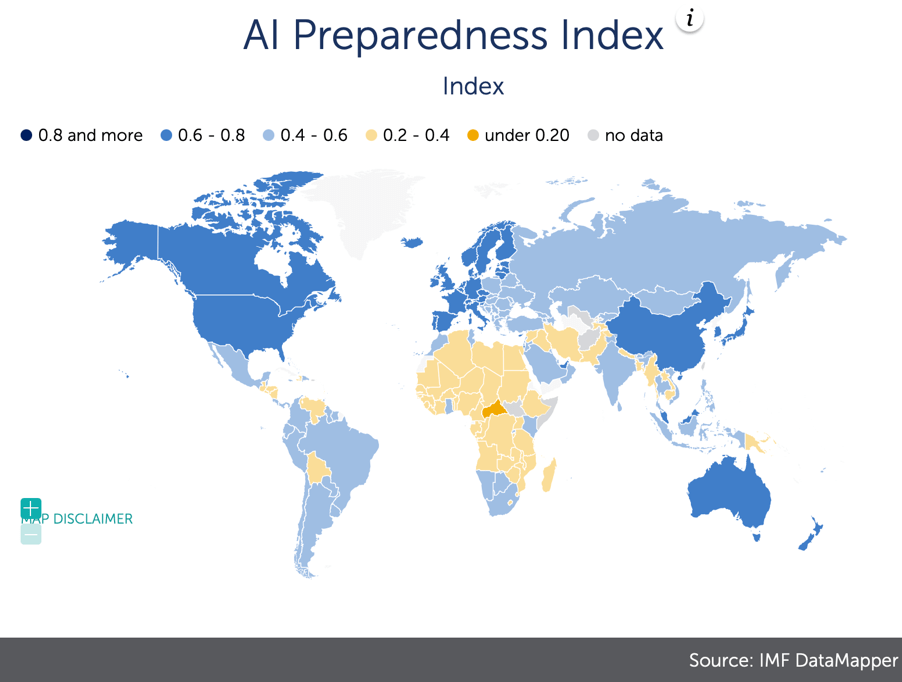

The IMF, in its AI Preparedness Index, suggests that there is a broad spread in the readiness of global economies for this coming wave of technological disruption:

Again, as things stand it seems that the greatest likelihood is for AI to exacerbate existing inequalities. Preparing for this major economic shift will demand fresh policies and investment. These are significant challenges for world economies, for companies as they embed AI into their workflows, and for global investors, to rise to.

See also: Learning from the stochastic parrots

Amazon resurrects worst of the industrial revolution

Just transitions and gilets jaunes

*I have my doubts about each of the A and the I in artificial intelligence: calling an activity ‘artificial’ when it depends on the horrific grinding work of many people to scrub its results seems inaccurate; and calling it ‘intelligent’ when it is simply a logic puzzle about the likelihood of putting one word after another – the stochastic parrots as described in that prescient article (I particularly like the analogy of Emily Bender, one of the authors of that article and a professor at the University of Washington, that AI is reproducing text in the way people might if they had unrestricted access to the National Library of Thailand but without pictures or dictionaries to enable them actually to understand or translate the language). A more recent article touching on these matters is the excellent Ask me Anything! How ChatGPT got Hyped into Being, which among other things states this fundamental truth: “LLMs are not designed to represent the world. There is no understanding by the artificial agent (chatbot) of the meaning of the output it creates. It is us humans who create that meaning.” More directly, the word soups that I have been presented with by colleagues show very clearly the limits of the technology in doing anything without clear instruction and precise pre-existing materials to work with.

See also: What’s a fair use?

I am happy for confirm as ever that the Sense of Fairness blog is a purely personal endeavour.

AI Will Transform the Global Economy. Let’s Make Sure It Benefits Humanity, Kristalina Georgieva, IMF, 14 January 2024

How Artificial Intelligence Will Affect Asia’s Economies, Tristan Hennig, Shujaat Khan, IMF, 5 January 2025

Asia and Pacific Regional Economic Outlook, IMF, November 2024

Thought experiment in the National Library of Thailand, Emily Bender, Medium, 25 May 2023

Ask me Anything! How ChatGPT got Hyped into Being, Jascha Bareis, 2024