Perceived unfair treatment is a driver not just of resentment but of outright conflict. Unfairness destabilises our world.

That’s the clear conclusion of some recent research by an IMF economist and a professor at Rice University in Houston in the US. Their focus is sub-Saharan Africa, a region with disproportionate levels of conflict and human suffering, whose violence fuels emigration and so more instability elsewhere. But it seems sure that while there unfairness fuels outright military conflict, the logic must be that in other parts of the world unfairness will drive unrest and discontent in different forms. The researchers refer to “conflict-inducing alienation”. That alienation can be seen in many countries of the world, not just sub-Saharan Africa.

But sticking first with their area of focus, the blog that accompanies the launch of the paper summarises the researchers’ findings:

“While various factors can fuel conflict, our research shows that discontent with state institutions among marginalized groups is a key driver of unrest in the region. Such distrust reflects perceptions that governments fail to address equity issues and inclusive growth—including the fair allocation of natural resources and human capital development… Poverty and underdevelopment alone may not fuel conflict. But those underlying factors are exacerbated by the experience or perception of social and economic exclusion, thus providing a fertile breeding ground for armed groups, necessitating urgent intervention.”

These countries in sub-Saharan Africa are of course among the first to experience the most brutal impacts of climate change, and this exacerbates the experiences of those at the edges of society. “Climatic fluctuations and food insecurity have been particularly acute in this subregion,” the paper reads. “Forecasts for 2023 indicate that nearly 142 million individuals in the region will confront acute food insecurity.” It should not be a surprise that “Food insecurity contributes negatively to trust in government.” Also unsurprisingly, the desperation that arises from this hunger drives individual actions, especially among those who have lost trust in governments. It must of course be noted that much of the poverty in the region is a legacy of colonialism.

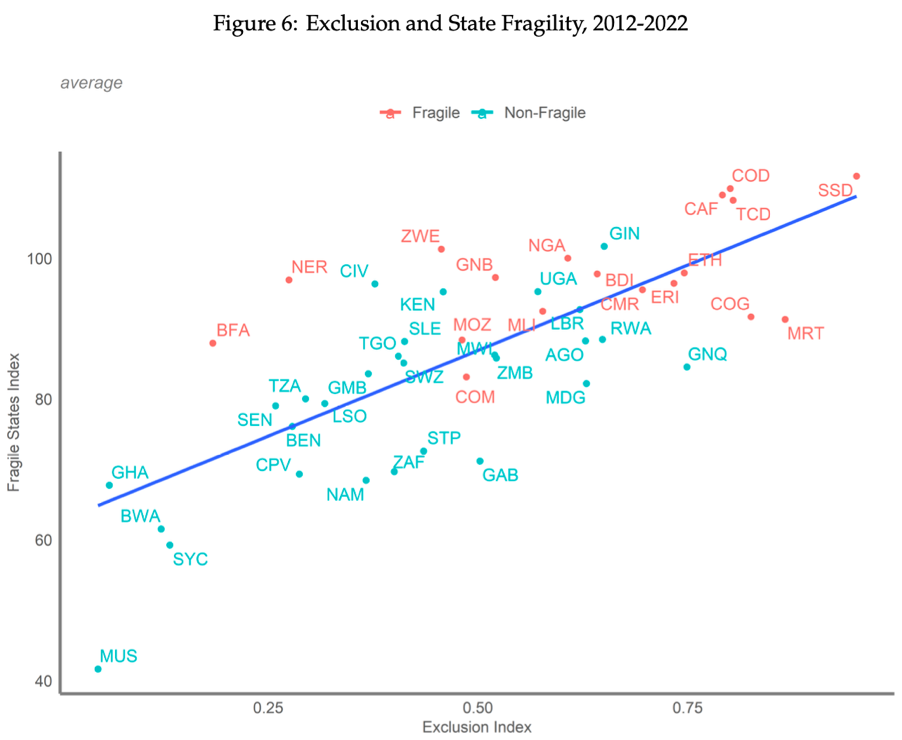

The consequences of this are stark. Essentially, there is a close correlation between the sense of exclusion and unfairness and the fragility of nation states and their susceptibility to conflicts of various forms. This chart from the paper illustrates the finding well:

The researchers conclude:

“Our findings show that the crisis of confidence experienced by marginalized groups towards state institutions is the primary driver of conflict. This crisis of confidence originates from the perceived failure of state institutions to safeguard interests, ensure justice, promote human capital development equitably, oversee fair allocation of natural resources, and encourage inclusive economic growth. Such institutional failures, contributing to perceptions of social and economic exclusion, invite conflict as they undermine the principles of fairness and inclusivity vital for sustainable development.”

These findings emphasise the importance of the Rule of Law in fostering trust in government and so in building the foundations for economic growth and investment. And there is a clear need to foster the basic expectations of a cohesive society in order to lean against these perceived unfairnesses: “These results suggest strongly that governments in the Sahel G5 as well as sub-Saharan Africa more broadly should focus their efforts on improving the quality of their institutions (reduce corruption and improve law and order) and provision of public goods (healthcare, education, air and water quality, food and shelter sufficiency) rather than focus primarily on macroeconomic variables such as the levels of economic growth and unemployment.”

The sense of being forgotten and left behind by government and wider society is greater for those at the geographic edges: “conflict is often concentrated near national borders where there tend to be more limited or insufficient public services, fostering feelings of exclusion”. Many of those national borders were drawn with the arbitrary straight lines of empire.

That sense of living at the periphery, having been forgotten by government and wider society, is of course not unique to people in the countries of sub-Saharan Africa. Many in all the countries of the world now feel left behind and peripheral. In sub-Saharan Africa these frustrations appear to be reflected in outright conflict but in other parts of the world the same sense of abandonment has inevitable, if different, consequences. The consequential violence can fuel crime, it can drive social division and anger in and with politics, but these are just other forms of the violence and dislocation that comes from people feeling that society no longer operates fairly to protect their interests.

Perceptions of fairness seem to be vital to hold states and their people together in peaceful coexistence.

See also: The Rule of Law is fairness

Lessons from Argentina, and Copperfield

Fraying Threads: Exclusion and Conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa, Hany Abdel-Latif, Mahmoud El-Gamal, IMF WP/24/4, January 2024

How Distrust of Government by Marginalized People Fuels Conflict in Africa, Hany Abdel Latif, Mahmoud El Gamal, IMF Blog, January 25 2024

The Rule of Law and investor approaches to ESG: Discussion paper, Paul Lee, Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law, September 2022

Note: in case it is not already sufficiently clear (looking at you, anonymous US company), I am happy to confirm that the Sense of Fairness blog reflects solely my personal views