The world of online dating turns out to be one of the most unfair economies there is. It is more winner-takes-all than all but the most unequal countries. Today is probably the least appropriate of days to reflect on this, which is why I’ve chosen to do so.

Perhaps I should say that this is not the usual male post railing at the unfairness of being ignored or unsuccessful on dating sites. There seem to be many of these, contrasting strongly with the usual female complaints about online dating, which appear to be more about the unpleasantness, weirdness and general flakiness of men. Having never used online dating I don’t have a personal complaint to make, but given the data suggesting it is one of the least fair economies in the world, it seemed an interesting area to explore on this blog.

Typically for my blog I reference proper academic articles. However, the sources I’ve been able to locate for this post are far from that, and the most entertaining very far indeed. Worst Online Dater’s ‘study’ included only a handful of participants and his method for gaining their participation certainly would not meet academic ethical standards — he posed as a highly attractive man on Tinder and then sought insights from some of the women who ‘liked’ his profile and started messaging.

His results were striking. He calculated a gini coefficient as high as 0.58 for Tinder’s economy of attractiveness and swipes. This is worse than the income gini coefficient of all but a few of the most unequal countries, such as South Africa. And his Lorenz curve of the Tinder economy demonstrates how far beyond even the unfairness of US income distribution this Tinder unfairness sits:

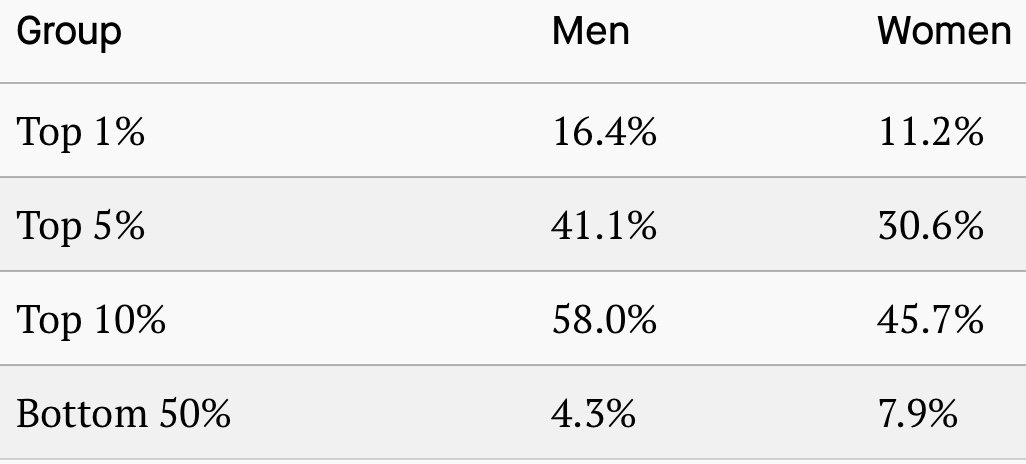

Though this brief study seems frankly pretty flaky, it is backed up by more robust datasets. The 12% of likes by women it identifies seems consistent with the 14% in more official reports, and with a finding according to OKCupid that women rate fully 80% of men as below average in terms of looks (perhaps contrary to expectations, men appear to have a much less skewed view as to the attractiveness of women). And more generally the inequality of distribution of likes does seem apparent elsewhere. Take Hinge [no? me neither], analysed by one of its own engineers, Aviv Goldgeier (according to an article on Quartz). On Hinge, apparently, users can like aspects of a profile rather than just the individual, meaning that there are potentially more likes to go around. However, their distribution is if anything less fair. The top 1% of men on Hinge receive 16% of all likes, and the top 10% nearly 60% of the total, leaving little to be shared among the bulk of men — the bottom 50% having to make do with less than 5%. The statistics for women are fairly similar but somewhat less extreme in each case:

This gives Hinge a gini coefficient of 0.73 for men, and 0.63 for women, still worse than Tinder’s unfair economy, though the article discusses this in comparison with country wealth gini coefficients meaning it finds further countries are more extreme in their unfairness than Hinge — including the US and UK. It is perhaps an interesting philosophical debate whether profile attractiveness online should be regarded as equivalent to wealth or income, but whatever, it is clear that these dating services are winner-takes-all and apparently highly unfair economies.

But it seems that, perhaps inevitably in a dating context, the largest driver of this unfair dynamic is gender differences. A search for complaints about the unfairness of (gay dating site) Grindr emphasise more that site’s perceived racism and possible exploitative charging than anything else. As an aside, that general tendency of a number of dating services to exploit the wishful thinking of customers by charging them for additional services is readily apparent — see for example the US Federal Trade Commission’s complaint against Match.com in relation to charges for contacting accounts the company allegedly believed to be fraudulent.

It turns out that online dating is seen by men to be unfair mostly because of very different male and female approaches to dating more generally. For example, on Tinder women swipe right (for ‘like’) 14% of the time, while men do so 46% of the time. Women are pickier than men: that is something that even those unversed in the online dating world will recognise as a general truth. So there are less likes to share around the men, and the distribution of them is rather inevitably not fair.

Happy valentines.

See also: Squid Game ‘fairness’

Tinder Experiments II: Guys, unless you are really hot you are probably better off not wasting your time on Tinder — a quantitative socio-economic study, Worst Online Dater, Medium, March 2015

Your Looks and Your Inbox, Christian, OKCupid official blog, November 2009

These statistics show why it’s so hard to be an average man on dating apps, Dan Kopf, Quartz, August 2017

FTC Sues Owner of Online Dating Service Match.com for Using Fake Love Interest Ads To Trick Consumers into Paying for a Match.com Subscription, US Federal Trade Commission, September 2019